Alcoholism, Colonialism and Neocolonialism in Africa

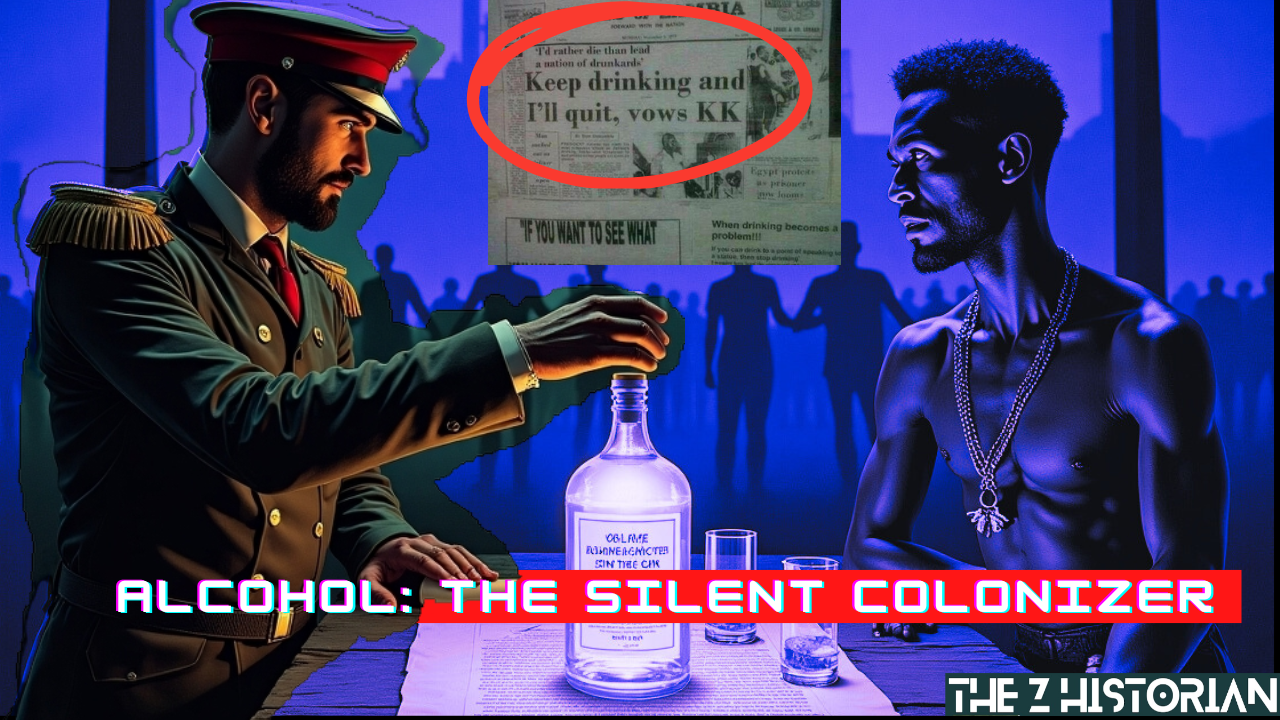

A Silent Weapon

The history of colonialism in Africa is usually told through muskets, missionaries, and merchants.

But lurking in the shadows of empire was in fact another tool for imperial conquest. Something more insidious and perhaps even more powerful—alcohol.

Indeed, the intoxicating elixir that is alcohol in its various forms became not only the lubricant of colonial conquest in African but the leash of Western control. From the gin-soaked treaties of the Gold Coast to the beer-fueled labor systems of Southern Africa, alcohol was as much a potent weapon as the maxim gun but perhaps with even more devastating and far reaching consequences.

For Africa, alcohol didn't just dull the senses; it dismantled cultures, eroded spiritual ties, and greased the wheels of exploitation.

As such, what seemed like a benign social lubricant or mere trade good became a silent weapon, shaping destinies and rewriting the fate of entire nations and peoples, one bottle at a time.

From a Symbol of Unity to a Tool of Oppression

For centuries, across the vast African continent, local brews were part of ritual, and often a sacred bridge between the living and the dead, a connection to the ancestors, a symbol of unity, and a measure of time itself.

In some Africa society, these brews were a staple, their thick and low-alcoholic content nourishing both the body and the bond between kin. Most brews were used during traditional ceremonies, ceremonies that were not about indulgence or intoxication—but about strengthening bonds and achieving collective meaning.

But then came the colonists, what we know as alcohol and the flood of intoxication—and with that deluge came chaos.

Where once fermentation was slow, deliberate, and tied to the rhythms of nature and community life, Europeans introduced distilled liquor—gin, rum, brandy—potent spirits, not brewed for communion but for commerce and above all, for conquest. And a drink that had once been sacred was turned into a shackles.

Without a doubt, the arrival of European liquor was not just, an introduction—it was an invasion.

Traditional brews were mild, and consumed in controlled, communal settings. But the colonizers flooded African societies with high-proof spirits, and with them came dependency, disorder, and decay.

First Weaken the Spirit, then take the Land

Indeed, though European colonizers did not introduce alcohol to Africa. They weaponized it.

But what's further interesting, is that they were not the first to do so on the African continent. Indeed, Alcohol has a long history as a tool of oppression going back thousands of years. Ancient civilizations in African, used it to keep entire populations under control even prior to colonialism.

In ancient Egypt for example, it is believed some Pheros encouraged heavy drinking among the masses to maintain a state of spiritual fog and compliance. They manipulated the belief that wine was a gift from ACYRUS using it to reinforce their power and control.

But it wasn't just the Egyptians, across ancient cultures in other parts of the world alcohol played a crucial role in maintaining power structures. Roman Emperors for instance perfected the Bread and Circuses approach distributing alcohol freely to keep the masses distracted. It wasn't just about having a good time, but control on a massive scale. Historians have further uncovered evidence of similar techniques in other ancient civilizations. But in colonial Africa, this strategy reached new depths.

One of the earliest and most glaring examples of alcohol's role in colonial exploitation was the infamous "gin-for-gold" trade along the West African coast. European traders, particularly the British, Dutch, and Portuguese, found that barrels of cheap, potent gin could work wonders in negotiations with African chiefs. In what could be considered one of history's most lopsided deals, African leaders were plied with liquor in exchange for gold, ivory, and even human lives in the transatlantic slave trade.

The 19th-century British explorer Richard Burton cynically observed that "gin and gunpowder" were the chief commodities in West Africa, a combination that ensured both intoxication and destruction.

The British Royal African Company, among others, actively used alcohol as a strategic bargaining chip, knowing well that a tipsy chief was more likely to sign away his land and people. However, some African rulers soon begun to see beyond the deception.

For example, In the Kingdom of Kongo, Portuguese traders flooded the region with aguardiente (a potent sugarcane liquor) in the 16th century. Initially, fermented palm wine was used in region for ceremonies and to honor ancestors, but the arrival of distilled spirits changed everything. King Afonso I (Nzinga Mbemba) witnessed firsthand how his people were becoming addicted and unruly under its influence. He wrote to the King of Portugal in 1526, pleading for restrictions on alcohol imports, warning that it was corrupting his kingdom and weakening his authority. But his cries were ignored—moreover a population lost in intoxication was easier to manipulate, exploit, and enslave.

Likewise, in Great Zimbabwe, traditional brewing of sorghum beer (known as hwahwa) was deeply tied to spiritual and social customs. It was used in ancestral veneration, rainmaking ceremonies, and communal gatherings—always consumed in moderation and under controlled circumstances.

However, with the arrival of Portuguese traders in the 16th century, distilled spirits were introduced, bypassing traditional brewing methods and undermining the spiritual order. Chiefs and spiritual leaders, who once held authority over alcohol distribution in sacred contexts, saw their influence eroded as foreign traders flooded local markets with stronger, more addictive liquors. This shift not only disrupted spiritual practices but also weakened traditional leadership structures, making societies more susceptible to colonial manipulation.

Without a doubt, the formula for the conquest of Africa was simple, and employed effectively by European colonizers: First, weaken the spirit of the Africans, ironically with intoxicating spirits. Then, break the will, and take their land.

Furthermore, in it what would come to be know as the the transatlantic slave trade, entire human lives were traded for liquor. African laborers in colonial mines and plantations were not paid in wages, but in rations of alcohol, ensuring they remained both physically exhausted and mentally subdued. The line between reward and restraint blurred, until drink became not just an escape, but a necessity.

But at what cost?

What was lost?

Some say, more than sobriety. More than tradition. What was lost was the connection to the African spirit a metaphysical disruption in African Psyche.

Lost in the Fog of Intoxication

In many African spiritual traditions, the body is not just flesh and blood—it is a vessel, a sacred conduit for energy, moyo, or ntu—the divine life force that connects the individual to ancestors, nature, and the higher realms. To be in harmony with this force is to walk in balance, to receive guidance from the unseen, and to uphold one's purpose. Therefore alcohol, does not merely intoxicate the mind—it disrupts, distorts, and severs special connection.

Among the Yoruba, for example, it is believed that one's Ori (spiritual head) must remain clear to align with destiny. A clouded mind weakens one's connection to their Orí-Inu (inner self), leaving them susceptible to confusion and external manipulation. In the Bantu cosmology, the life force (ntú) flows through all living beings, but alcohol consumption is seen as a poison to this energy, corrupting the harmony between body, spirit, and the ancestral realm.

Indeed, when used without sacred intention, alcohol does not elevate—it drowns. It does not connect—it isolates. It does not open the spirit—it weakens it, leaving it susceptible to negative forces. This is why colonial powers encouraged the reckless distribution of strong liquor:

For a people unmoored from their spiritual anchors, lost in the fog of intoxication, are easier to break, easier to bend, and far easier to rule.

Thus many, traditionalist see the disruption of African societies through alcohol as not just about physical addiction—but metaphysical enslavement. They believe that when the mind is clouded, one's intuition is dulled. When the life force is poisoned, one's destiny is derailed. And when the sacred bond between the self and the ancestors is severed, a people lose their spiritual armor—becoming vulnerable to forces that seek to control them.

Now connect this to the rise of Beerhalls in the late 1900s.

The Haze of Beerhall Stupor

By the early 20th century, beerhalls were no longer just places of drinking—they were battlegrounds of the mind, weapons in the arsenal of colonial rule. For instance, the mining compounds of Northern and Southern Rhodesia, in the streets of Johannesburg and the segregated townships of Durban, these state-controlled drinking dens became the perfect tool for domination. The colonizers understood a simple truth: a people drowning in intoxication would struggle to rise in resistance.

Thus, these beerhalls which some African mistaken took for avenues to promote equality and an opportunity to experience European lifestyle, were never meant to serve the African people. They were designed to siphon wages, break spirits, and fracture the communal bonds that once held African societies together. The colonial government outlawed traditional brewing—the sacred craft of African women—and replaced it with their own system of control.

Alcohol, once poured in libations to honor ancestors, now flowed freely to pacify laborers, deaden their grievances, and empty their pockets.

And so is how the wages earned in the brutal mines and factories found their way back into colonial coffers, as men stumbled from the depths of mineshafts into the haze of beerhall stupor.

But oppression breeds defiance. The very spaces meant to dull the African mind became sites of awakening. Women, the guardians of ancestral customs, refused to watch their men be consumed by colonial poison. In 1929, the streets of Durban erupted in fury as Zulu and Xhosa women led a powerful boycott against beerhalls, smashing barrels and demanding the restoration of their rightful place in society. Similar uprisings spread across Southern Africa, transforming spaces of enslavement into stages of rebellion.

The colonizers had underestimated the resilience of a people whose spirits ran deeper than the intoxication forced upon them. For every beerhall they built, they unwittingly ignited the fire of resistance.

Temperance Movements: When Sobriety Became Subversion

As colonial officials profited from African inebriation, local resistance movements began to recognize the sobering truth—literally. Anti-alcohol movements sprang up as part of broader nationalist struggles. Leaders like John Chilembwe in Nyasaland (now Malawi) and Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya saw alcohol not just as a vice, but as a tool of oppression. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church and various Islamic communities had long resisted colonial liquor policies, framing abstinence as an act of cultural and political defiance.

In a fascinating twist, some colonial authorities, especially the British in the early 20th century, tried to curb alcohol consumption—less out of moral concern and more because a permanently drunk populace was less productive. The irony, of course, is that many of these same officials had been complicit in flooding African societies with alcohol just a few decades prior.

After Zambia gained independence in 1964, alcohol abuse remained a significant issue that contributed to social and economic challenges. President Kenneth Kaunda, in his early years of leadership, expressed concerns over the rise in alcoholism and its negative impact on the newly independent nation. This problem was particularly prevalent in the urban areas where newly established industries and the mining sector attracted a large workforce, many of whom turned to alcohol as a means of coping with the stresses of rapid urbanization and industrialization.

President Kaunda was committed to building a self-reliant and prosperous nation, and he recognized that the widespread drinking culture undermined this vision. It was causing a number of social issues, including high levels of absenteeism in the workforce, family breakdowns, and a reduction in productivity.

In 1969, President Kaunda nearly resigned over the extent of alcoholism in the country. He was frustrated by the challenge of managing this growing problem, which seemed to defy his attempts to instill national pride and self-discipline. His leadership was under intense scrutiny, and he considered stepping down, but ultimately, he chose to stay on, reaffirming his commitment to the nation's future.

President Kaunda's government took several steps to combat the issue, including imposing restrictions on alcohol sales and introducing educational campaigns to raise awareness about the dangers of excessive drinking. Despite these efforts, the challenge of alcoholism persisted for many years, reflecting broader issues related to social dislocation and the complexities of post-colonial nation-building.

The Legacy of Alcohol as a Colonial Tool for Oppression

Today, the legacy of alcohol as a colonial tool for oppression lingers in many African societies. The liquor industry remains thriving dominated by multinational corporations, many with roots in colonial-era enterprises. The economic dependency cultivated during colonial rule has translated into modern-day challenges, where alcohol abuse remains a significant social issue in many parts of the continent.

In the final analysis, alcohol, like many other tools of colonial control, wasn't just about the substance. It was about power, manipulation, and disruption—disrupting the very fabric of African societies that had been carefully woven over centuries.

It wasn't merely a drink; it was a weapon designed to erode unity, to displace the connection between mind, body, and culture, and create a distraction from the real struggles of liberation and self-determination.

And yet, long after the formal end of colonial rule, the question endures: If Africa continues to wrestle with the grip of alcohol, now controlled by multinational corporations, can we truly claim to be free?

Or have we simply transitioned, from one form of oppression through alcohol, into another?